African American History Month

The significance of African American History Month has many meanings for NYSNA. In one sense, we celebrate our very own NYSNA members of African American heritage and their extraordinary contributions to society, both in the delivery of quality healthcare and in our activities that support equal access to quality care and celebrate our cultural diversity. We also see the historic contributions of African American nurses in the making of this nation, a proud and accomplished history with stories of great heroism. These stories still do not have their deserved place in the recounting of our nation’s past and we recognize the importance of telling them as part of the history of nursing.

There is yet another dimension to the importance of African American History Month to NYSNA. It is rooted in our connection to and place in the labor movement in the U.S. We recognize with great pride how the organizations of working people fought for civil rights and social justice. Labor has a proud and just place in the annals of African American History.

A time to reflect

Recent events in the U.S., notably in Charlottesville, Virginia, where white supremacists marched through a historic district with the intention of attacking African Americans and promoting symbols of slavery, are a shocking reminder of how a small, but bigoted and hateful segment of society views race relations. These actions serve to heighten the importance of our union using our moral authority — as a trusted voice on community health — during this African American History Month. We can remind New Yorkers and the nation of the contributions of African American nurses and union members to our nation’s history of social progress and diversity.

Labor stood tall with African Americans in protests, then and now

The displays of bigotry in 2017 triggered an outpouring of support for African Americans from a coalition of religious, community, public health and many other Americans, including virtually all of organized labor, NYSNA among them.

The list of support fills volumes, but one significant historic event should be brought forward in every discussion of African American History Month.

The Memphis sanitation strike of February 1968 in Memphis, Tennessee, served as a rallying cry against inequality in the workplace and the deadly conditions that can result. On February 1, two Memphis garbage collectors, Echol Cole and Robert Walker, were crushed to death by a malfunctioning truck. Their deaths were the culmination of a long pattern of neglect and abuse of black employees. On February 11, over 700 attended a union meeting and voted — unanimously — to strike. On the 13th, 1,300 African American men struck outside the Memphis Department of Public Works.

The sanitation workers, led by a dynamic organizer from their ranks, T.O. Jones, drew support from the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME), Local 1733, demanding union recognition, better safety standards and decent wages.

The workers were up against Mayor Henry Loeb, who was determined to fight the union and keep black workers on the job in appalling conditions and low wages. In fact, these sanitation workers earned wages so low that many were on welfare and hundreds relied on food stamps to feed their families (a practice, it should be noted, that had continued — until very recently — at America’s largest employer WalMart, as low wages there forced workers to turn to food stamps to survive).

Support for the Memphis sanitation workers grew. The NAACP passed a resolution in support.

Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. arrived on the scene on March 18, to address a crowd of 25,000 — the largest indoor gathering the civil rights movement had ever seen. Addressing the crowd of labor and civil rights activists and members of the powerful black church, King praised the group’s unity. “You are demonstrating that we can stick together. You are demonstrating that we are all tied in a single garment of destiny, and that if one black person suffers, if one black person is down, we are all down.”

There was chaos surrounding this struggle, as a belligerent mayor and his police resisted a strike settlement.

Dr. King assassinated in Memphis

On April 3, Dr. King returned to Memphis. “We’ve got to give ourselves to this struggle to the end,” he told gatherers. “Nothing would be more tragic than to stop at this point in Memphis. We’ve got to see it through.”

“Like anybody,” he said, “I would like to live a long life — longevity has its place. But I am not concerned about that now.… I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land.”

This heroic visionary was shot and killed in Memphis the next day, April 4.

On April 8, more than 40,000 people led by his widow and including movement and union leaders marched silently through the city. AFSCME pledged support until “we have justice.”

The union was recognized and a deal was reached on April 16.

It was emblematic: a bitter struggle in an American city with a long history of segregation, a police force culled from the Ku Klux Klan and unfair treatment of African Americans in all aspects of work and life had been met head-on by courageous black strikers, union support, religious and community activism and extraordinary leadership.

That is the labor legacy of African American History all union members remember this month.

Prominent African American nurses

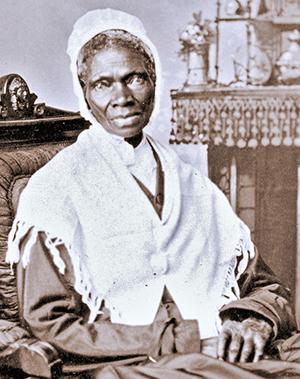

The Civil War was a training ground for African American nurses. Black women born into slavery who became nurses during this time included Sojourner Truth (1791-1883) and Harriet Tubman (1822-1913), both known as abolitionists and the latter for her historic role in the Underground Railroad. Both also took on roles as nurses for soldiers during the Civil War. Susie Baker King Taylor (1848-1912), liberated by Union troops in 1862, turned to nursing sick and wounded soldiers, as well. She went on to become president of the Woman’s Relief Corps, a veteran’s association carried through to civilian life. She is remembered for this quote from her 1902 memoir: “It seems strange how our aversion to seeing suffering is overcome in war, how we are able to see the most sickening sights… with feelings only of sympathy and pity.”

Pioneering African American nurses

In 1900, Jesse Sleet Scales became the nation’s first black public health nurse. From tuberculosis in New York City’s African American community to childbirth, chicken pox, heart disease and cancer, her crusading efforts expanded the breadth of public health for the black population.

African American nurses advance

Brig. Gen. Hazel Johnson-Brown, RN, PhD (1928-2011), joined the Army Nurse Corps in 1955 and went on to oversee nursing operations at hundreds of Army medical centers, community hospitals and clinics. The daughter of a tomato grower, Brown was originally rejected for nursing school because of her race. It is said that school authorities informed her, “We’ve never had a black person in our program and we never will.” Brown was the first black woman to become a general in the U.S. Armed Forces.

Booker T. Washington established a two-year nursing program at Tuskegee University in Alabama in 1892. In 1948, the School of Nursing’s new dean, Lillian Holland Harvey, RN, EdD (1912-1950), started Tuskegee University’s baccalaureate nursing program. Its first graduating class took their degrees in 1953.

Enduring issues

Serena Williams, a world-renowned tennis champion, endured life-threatening complications after giving birth. She developed pulmonary embolisms but had to advocate vigorously with her healthcare professional team — who initially dismissed her self-assessment — to get the right tests and the right medicine. Further complications ensued: a ruptured C-section wound from coughing due to the embolisms and a hematoma in her abdomen from the blood thinners. She needed six weeks of bedrest even after she was discharged.

Tens of thousands of women face dangerous or life-threatening, pregnancy-related complications each year, but black women are three to four times as likely as white women to die from such complications.

Ending health disparities

Research is beginning to show that chronic stress from encountering discrimination affects the health of black women of all economic groups — even athletic stars like Ms. Williams. This can be compounded by poor access to pre- and postnatal care, inadequate medical treatment in the years preceding childbirth and the challenge of getting healthcare professionals to take their self-assessments seriously. There is much work to do to achieve equal access to quality care and reduce disparities in health outcomes.

“We have seen some remarkable improvements in death rates for the black population in the past 17 years,” wrote Leandris Liburd, PhD, MPH, MA, associate director of CDC’s Office of Minority Health and Health Equity. “Important gaps are narrowing…. However, we still have a long way to go. Early interventions can lead to longer, healthier lives. In particular, diagnosing and treating the leading diseases that cause death at earlier stages is an important step for saving lives.” NYSNA nurses have made historic contributions to community health and will continue to do so into the future.

Unions join #MeToo

African American and other women are now turning to their unions to put a stop to sexual harassment on the job. They know that #MeToo is meant for all women, on every job and in every setting.

A prominent example of African American women, joined by Latina coworkers, was in Chicago where hotel workers represented by UNITE HERE banded together in a movement to stop sexual harassment.

They found that well over half of hotel workers reported harassment from guests; their #HandsOffPantsOn campaign demanded that management equip hotel maids with panic buttons and ban guests who sexually harass a worker.

The collaboration of unions in the civil rights and social justice movements of our day continues, with African American women at the forefront.

How the Month was launched